The subject of my book, Carolina Clay, is the extraordinary 19th-century potter known as Dave. He occupies a place in the history of Southern folk pottery that is close to legendary. He is revered for the quality of the pots that he made, for the size of these containers, some of which could hold up to 40 gallons, and for the inscriptions, often rhyming couplets, that he sometimes wrote on them. More than 30 of his verses survive.

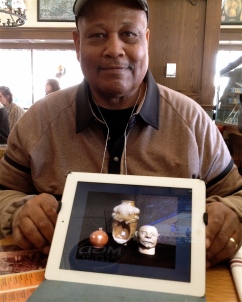

Once in a great while, a pot bearing a “new” message from Dave is discovered. That recently happened, causing phone calls and e-mails to shoot throughout the Southern pottery world. Because the location of the pot was not made known and its owner preferred to remain anonymous, I thought I had no chance of seeing it. To my delight, however, the owner has allowed it to be exhibited temporarily at the South Carolina State Museum in Columbia.

The State Museum is a repository of wonderful artifacts, each of which helps tell the complex, sometimes crazy story of life in the state that in 1860, shortly after Secession, James Pettigru characterized as “too small for a republic, too large for an insane asylum.” Dave’s work perfectly conveys his portion of this idiosyncratic story: he lived at a time when it was forbidden by state law to teach slaves to read or to write, yet he managed to publish his inner thoughts in the most public way available to him—on the sides of his pots.

Slaves had sought the ability to read ever since the earliest days of the Atlantic slave trade. They yearned to “make the book talk,” as they saw their owners do. It would seem a simple thing for masters to share the knowledge of reading with their servants, but slaveholders understood that even the smallest education could enable a slave to make decisions on his own, becoming in the process less a slave and more a danger to the slave system. Masters consequently went to great lengths to keep those they owned in ignorance.

In the early decades of the 19th century, however, some highly religious slave owners chose a different path. According to Drake family members who still live in South Carolina, Dave’s owner, Harvey Drake, made the decision to give basic reading instruction to him and others among his slaves. He took this step so that they could read the Bible and find salvation. These simple lessons may have changed Dave’s religious life; they certainly changed his intellectual life. He could now decipher puzzling letters, words, even sentences, an ability denied to what historians believe was 95% of Southern slaves.

He also learned to write. He probably had to acquire this skill on his own, by hook or by crook, for writing was considered much more dangerous by slave masters than reading. A slave with this ability could fashion himself a pass, for example, and escape from the state.

Dave may have become interested in poetry during a brief period in his early life when he was put to work at a newspaper, called the Edgefield Hive. Perhaps he was inspired by the weekly verses that ran in the paper. This much we can be sure of: from almost his earliest known inscriptions, he was creating rhymes and organizing his words in poetic forms.

A few days ago, I drove to Columbia from my home in Edgefield, South Carolina, which is also where Dave lived. It takes about an hour and twenty minutes to get there. The museum is housed in an enormous 19th-century brick warehouse. The building somehow managed to survive the inferno that in 1865 destroyed most of the rest of the capital. The fire was set (take your choice here) by invading Yankees or by retreating Confederates or by accident.

There’s something to capture the attention on each level of the museum’s vast, open interior. As I climbed the stairs, I saw a life-sized model of the railroad train known as “The Best Friend of Charleston.” The train was constructed to run on what was once the longest rail line in the world, starting in Charleston and extending across the state to Hamburg, a little town on the Savannah River opposite Augusta, Georgia. The successor to this engine was probably the one that ran over Dave in about 1835, severing his leg from his body.

On the level above that, almost within sight of the train, is the display case that holds Dave’s pot. The ovoid shaped jar, just over 19 inches tall, was used for food storage. Covered with a hard, alkaline glaze, it has a tan color, which is mottled with brown and gray. The glaze is partly missing from the rim on one side and from the base of the opposite side, the two places where Dave held the jar as he dipped it into the glazing solution. What seems to have been a hard life has chipped off both its lug handles. It is dated 22 August 1834.

Here’s the couplet that Dave wrote on it:

oh the moon + the stars

hard work to make big Jars

These new words fascinate me. It’s wonderful to hear Dave talking about the actual process of making a pot. Though he speaks about his finished containers in several other instances—he calls one of his largest pieces, “Great & Noble Jar”—this is the only known occasion in which he describes the backbreaking nature of the whole undertaking: “hard work,” he calls it. On the 22nd of August in the potting shed of his owners, Reuben Drake and Jasper Gibbs, it must have been steamingly hot work, as well.

In admiring Dave’s creations, it’s easy to forget that they are the product of a slave system. He wasn’t making them out of choice. Turning pots was the job he had been assigned and he did it day in and day out for much of his long life. Others worked in the fields or in the houses of their owners; because Dave’s owners were pottery manufacturers, he made pots.

Dave begins this couplet with a reference to the skies above: “oh the moon and the stars.” I can’t help but wonder if this first line might actually be an exclamation, similar to, “My stars!” or “Heavens above!” In that case, the verse might be saying something akin to, “Great day! What a hard way to make a living!” Not a complaint, more a statement of unavoidable fact. Surely, it would have been a relief for Dave to speak out like that, even if silently.

Then again, he might not have had that in mind at all. You never know with Dave. For every interpretation of one of his verses, there are half a dozen others waiting to be argued for. (The Chief Curator of Art at the State Museum, Paul Matheny, reads this inscription differently from the way I do. I’ll be telling about my conversation with him in my next posting.)

The couplet is written in a somewhat cramped script, very carefully incised into the clay, perhaps reflecting how new all this was to him. It runs between the two handles on one side of the jar. The date is inscribed once following the verse and again on the opposite side. Verses composed later in Dave’s life are often written in a more confident, even florid hand.

The jar sits in its case beside another poem pot by Dave, one that is part of the State Museum’s permanent collection. The two jars are almost twins. This one, however, is in near-perfect condition, with both of its lug handles still in place. It is inscribed with Dave’s oldest known verse, dated 12 July 1834, written only six weeks before the one I’ve just described. It reads:

put every bit all between

surely this Jar will hold 14

Dave’s message would have been perfectly clear to Edgefieldians in 1834: Pack this 14-gallon jar tightly with fresh meat. It is, in effect, a short set of instructions on how best to use the pot.

Because erasing mistakes is not practical when writing on damp clay, Dave’s corrections are permanent parts of his poems. In the July verse, he inadvertently left out the word “bit” when he wrote it and came back to add it above the line. In the August verse, he spelled “moon” with only one “o,” then carefully added another one just above it. I’ve always found original manuscripts—with infelicities scratched through and words added in the margins—to be more interesting than the final, perfect product. With computers, of course, all history of the struggle that goes into forming a writer’s paragraphs is lost. Dave’s process, mistakes and all, has been preserved for us in clay.

These two poems were written just a few months before the South Carolina General Assembly, fearing bloody uprisings similar to the one led by literate Virginia slave Nat Turner, passed the harshest anti-slave-literacy law in the state’s history. The law specified that a white person convicted of teaching a slave to read or write could be sent to jail; a slave convicted of teaching another slave could be given up to fifty lashes with a whip. Encouraged by this extreme position, some owners took it upon themselves to repress the budding desire for knowledge that they sensed in their slaves. They promised severe beatings to any slave found with a book or with pencil and paper. Some threatened to cut off the forefinger of any slave who learned to write.

Dave continued to write openly on his pots during this dangerous period. This could have been because his owners, as far as we can tell, were less rigid than the “fire-eaters,” who sponsored the legislation. However, I tend to think it was the result of a strategy that Dave, himself, developed: he welcomed visitors at his wheel; he entertained and informed; he produced handsome jars, used impressive words—and apparently charmed everyone around him. Even the editor of the Edgefield Advertiser noted what he called “an intelligent twinkle in his eye.” If Dave did all this as a conscious defense against those who might use the law against him, he succeeded brilliantly. By hiding nothing, he seems to have been able to freely continue the conversation—word after incised word—that he had started with the world.

Dave’s new poem pot will be on display at the State Museum in Columbia for the remainder of 2012. There’s also an excellent exhibition there called “Tangible History: South Carolina Stoneware from the Holcombe Family Collection.” It’s the first extensive showing of the pottery collected by the Holcombes—mother, father, and two sons. It contains a number of fine examples of Edgefield pottery, including a wonderful, signed jar by Dave.

The South Carolina State Museum is located at 301 Gervais Street in Columbia. For opening hours and other information, visit http://www.scmuseum.org. While in Columbia, you’ll find more fine examples of South Carolina folk pottery at the McKissick Museum. It’s at 816 Bull Street on the campus of the University of South Carolina. (Check the museum’s renovation schedule at http://www.cas.sc.edu/mcks/.)